Written by Vincent Diringer, Content Editor, Sustainability

As part of the global political response to climate change, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) holds a yearly Conference of the Parties (COP) in one of its signatory nations. This has happened every year since 1994, except for 2020, when the global COVID-19 pandemic delayed the summit by a year. The yearly COPs serve as an opportunity for negotiators to debate the next set of climate goals, and for decision-makers to take stock of the progress they’ve achieved so far [1, 2]. Following two weeks of negotiations on key topics, the summit concludes with an agreement on climate action like the Paris Agreement (COP21), or simply with a statement outlining the developments from the COP, like this year’s Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan.

Outside of the negotiations taking place at the summit, pavilions within the COP campus accommodate delegations from global governments, civil society, and special interest groups. This setting provides opportunities for networking and knowledge-sharing between a wide range of stakeholders, and can be the precursor for the development of private and public sector partnerships towards sustainability, economic development, and climate action. COP remains a relatively closed event, with accreditation for the summit limited and reserved for diplomats and UNFCCC-recognized organizations [2].

What does this mean for individuals?

The UNFCCC COP dictates the speed and scope of global climate action. Therefore, this yearly summit has the ability to set new frameworks, goals, and developments capable of affecting governments, companies, and individuals. For example, the Paris Agreement has served as the key reference for climate action since its creation in 2015, and has gone on to influence the transition to net zero. Other mechanisms can be developed that can impact individuals at a policy level, such as climate finance for Loss & Damage (L&D) which provides technical and economic support to climate-vulnerable countries affected by climate change impacts.

While policy negotiations and civil society meetings are the main activities at COP, global politics and corporate agendas influence the outcome to the point that the summit has been called ineffective and a vector for greenwashing. Combined with slow action on climate and limited advocacy for evidence-based solutions established on scientific research, COPs are increasingly seen as having a limited effect on climate due to the toothless nature of international politics [3-5].

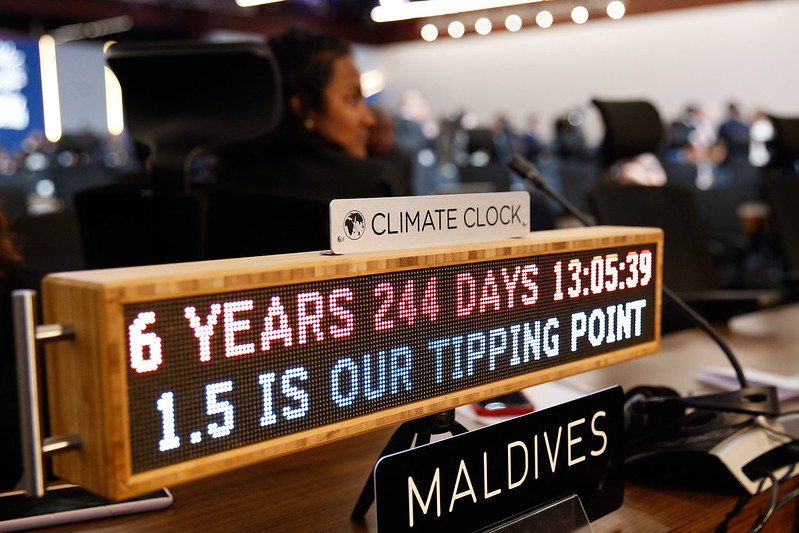

As outlined by University College of London Professor Bobby Bannerjee [4], “After 27 years of negotiations, conflicts and breakdowns, the world’s nations have basically agreed: (1) climate change is a serious problem; (2) something must be done to fix it; (3) rich nations should do more; and (4) based on the Paris agreement of 2015, every country should set their own emissions goals and do their best to meet them. The UN claims that the Paris agreement is “legally binding”, but there are no enforcement mechanisms or penalties for countries in breach. Even current pledges will not be enough to meet the target to restrict global warming to the 1.5℃ target agreed in Paris.”

Outcomes of COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh

Professor Bannerjee’s comments are an accurate summary of the outcomes of COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh [3-5]. As a delegate attached to the Climate Youth Negotiators Programme (CYNP) and youth advocacy non-for-profit ClimaTalk, I was in Egypt shining a light on young people and their roles in policy-making. While this COP was the first to have youth, indigenous people, and climate justice pavilions – all of which were amongst the most popular ones over the course of the two weeks – there was a permeating feeling that these must progress from tokenistic participation to actual impact within negotiations. Over the course of my time there I heard multiple observers and negotiators highlight how despite an increased amount of youth being represented at the summit, there continued to be pushback against including young people in decision and policy-making.

While there may have been blockages at the negotiating table, young people were amply represented amid civil society and government delegations. Several young entrepreneurs expressed that they saw COP as a way of building bridges with like-minded individuals and changing the world via their projects, rather than via slow diplomatic processes that are easily hampered. Actions speak louder than words was the adage that seeped through conversations, and young people were clearly ready to take things in hand.

Although diplomats were able to find an agreement on L&D (Loss and Damage) after several decades of negotiations, the final text was seen as a step back in terms of actions especially considering the advice provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and growing support to condemn and drastically reduce the usage of fossil fuels. COP27 hosted one of the largest contingents of fossil fuel delegations the summit has seen, and featured a pavilion from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), this in tandem with Coca Cola announcement as a sponsor has added fuel to the debate of large-scale greenwashing and climate inaction at major international events [6-8].

One thing has been made clear: businesses and individuals have an opportunity to stir change from the bottom-up. Capable of making their own decisions and working collaboratively with other like-minded organizations and persons willing to make a difference, companies have an opportunity to be the leaders in climate action – have you considered how you could enact change in your community?

Key Takeaways:

- The yearly COPs serve as an opportunity for negotiators to debate the next set of climate goals, and for decision-makers to take stock of the progress they’ve achieved so far [1,2];

- While policy negotiations and civil society meetings are the main activities at COP, global politics and corporate agendas influence the outcome to the point that the summit has been called ineffective and a vector for greenwashing [3-7]; and

- Although diplomats were able to find an agreement on L&D after several decades of negotiations, the final text was seen as a step back in terms of actions [5].

References

[1] UNFCCC, 2022, “Conference of the Parties (COP)”, United Nations.

[2] Malek Romdhane & Vincent Diringer, 2021, “What is COP?”, ClimaTalk.

[3] Gloria Dickie and Simon Jessop, 2022, “COP27 – Corporate climate pledges rife with greenwashing – U.N. expert group”, Reuters.

[4] Bob Bannerjee, 2022, “Why COP27 should be the last of these pointless corporate love-ins”, The Conversation.

[5] Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Josh Gabbatiss, Joe Goodman, Simon Evans and Zizhu Zhang, 2022, “COP27: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Sharm El-Sheikh”, Carbon Brief

[6] Ruth Michaelson, 2022, “‘Explosion’ in number of fossil fuel lobbyists at Cop27 climate summit”, The Guardian.

[7] Esme Stallard, 2022, “COP27: Activists ‘baffled’ that Coca-Cola will be sponsor”, BBC.

[8] OPEC Fund, 2022 “COP27 Overview” OPEC.